rewrite this content using a minimum of 1000 words and keep HTML tags

Aree Sarak/iStock via Getty Images

No, you can’t blame it all on El Niño. – Tom di Liberto, NOAA

A brief update

When we published the last Absolute Return Letter in early July, I half-promised to complete this mini-series on climate change no later than in October. Now, a couple of months later, and being knee-deep in research on various climate issues, I no longer feel that is realistic, particularly not as virtually every Absoluter Return Letter we publish is subject to our self-imposed limit of 1,500 words.

In our July letter, I listed the three factors which have caught (most of) my attention up to this point:

El Niño. The fact that the Northern Hemisphere is warming much faster than the Southern Hemisphere. Earth’s current position in the Milankovitch cycle, which explains changes in orbital characteristics, which again may explain changes in the climate.

In principle, each of those three issues probably deserves its own letter. However, the estimated impact of the Milankovitch cycle, although quite severe longer term, is minimal over the short to medium-term. I have therefore decided to incorporate it in next month’s letter which is otherwise dedicated to various hemisphere predicaments. I will then cover something altogether different in the November letter before I return to the climate issue in December with some personal thoughts.

What is El Niño?

El Niño is a natural climate phenomenon that originates in the Pacific Ocean and impacts the climate worldwide. In some parts of the world, the impact is clearly measurable and quite well understood, whereas in other areas the impact is subtle. The name “El Niño” refers to the warming of sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical parts of the Pacific Ocean where the El Niño phenomenon occurs every few years. Trade winds normally push warm surface water westward towards Asia but, when those trade winds weaken, warm water instead spreads east towards South America.

In South America, the warmer Pacific ocean brings heavy rains and floods to countries like Peru and Ecuador. In Asia/Pacific, Australia and other countries experience droughts and wildfires. In the US, the outcome is more mixed. The West Coast can expect wetter winters and heightened storm activity. Northern parts of the US and Canada can expect milder winters whereas, along the Gulf Coast and in the southeast, conditions are wetter than normal.

An average El Niño lasts about 12 months, but there are plenty of examples of them lasting longer. The most recent El Niño began in 2023 and continued for much of 2024. 2025 has, so far, been pretty much ENSO-neutral.

The joint name of El Niño and its ‘cousin’ La Niña is ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation). The term ”ENSO-neutral” refers to the state in the ENSO cycle where neither El Niño nor La Niña conditions prevail. For your information, La Niña is the opposite of El Niño. Cooler sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific leads to widespread changes in weather patterns complementary to those of El Niño but less damaging.

As most El Niños lead to plenty of extreme weather, it goes without saying that the economic impact can also be quite severe. The agricultural and insurance industries are the two industries most exposed to El Niño, but other industries may be affected too. Electricity production, for example, may suffer – particularly when generated by renewable energy forms.

The impact of El Niño in 2024

Nearly everyone thinks last year was characterised by exceptionally warm weather and, yes, it was extraordinarily warm in 2024, but one shouldn’t draw any conclusion without taking El Niño into account.

As you may recall, a few years ago, the UN capped the global average temperature rise to +1.5°C degrees over pre-industrial times, arguing that a bigger rise than that would lead to more extreme weather events, increased risks to ecosystems and an intolerable rise in sea levels.

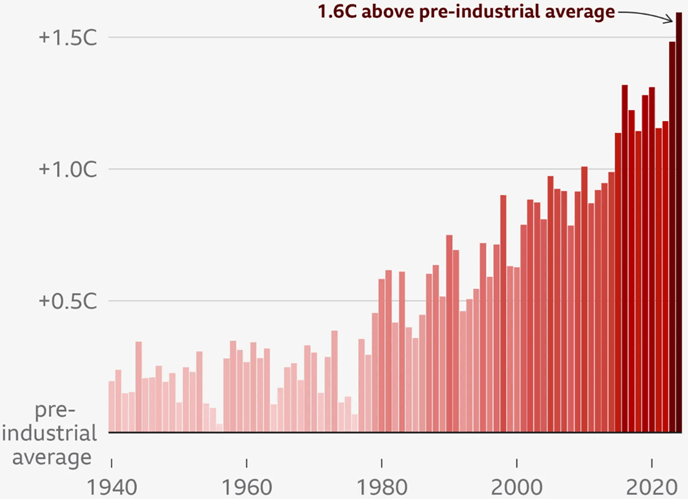

According to WMO, that threshold was exceeded for the first time in 2024. The global average temperature for the entire year was 1.55°C above pre-industrial levels. While the limit had previously been exceeded for shorter periods of time, 2024 was the first full year for that to happen (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Global average temperature over pre-industrial average

Sources: ERA5, C3S/ECMWF, BBC

The 2023-24 El Niño was one of the most powerful in post-industrial history. It peaked between November 2023 and January 2024, when sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific were more than 2°C higher than usual, which is about the most ever seen.

The higher sea temperature impacted global weather patterns and contributed to record-breaking temperatures in both 2023 and 2024. However, before you draw too many conclusions, you should know that the global average temperature rises about 0.07°C for every 1°C degree rise in the eastern Pacific, i.e., the El Niño-adjusted rise last year was 1.55°C – 0.14°C = +1.41°C.

What can you expect from El Niño / La Niña in 2H25 and 2026?

WMO, NOAA and IRI, all in the elite of leading meteorological research organisations, agree that 2H25 is 65-70% likely to deliver ENSO-neutral weather conditions. They also agree that, should that forecast turn out to be wrong, 2H25 will most likely deliver weak La Niña conditions. In other words, 2025-26 is likely to be affected very differently from 2023-24 by this weather phenomenon which, in itself, should open the door for plenty of discussions (and disagreement) amongst so-called experts.

If meteorologists are correct, i.e., if we are facing ENSO-neutral, possibly weak La Niña, conditions over the next 12 months, 2025 and 2026 won’t be as warm as 2023 and 2024. In North America, the winter storm track may shift northward. The Pacific Northwest, Upper Midwest, and Northern Rockies may see wetter and snowier winters, and southern parts of the US (e.g. California and Arizona) are less likely to see the enhanced precipitation normally linked to El Niño. Atlantic hurricane activity will likely be more active than usual, which will affect both North America and Europe and, in Australia, Southeast Asia and Africa, a weak La Niña (if it occurs) should lead to increased rainfalls, increased flood risks and heightened cyclone activity.

However, because of ongoing climate change, whether El Niño or La Niña prevail, both 2025 and 2026 are expected to remain among the warmest years on record. I should add that some climate change deniers argue that the phenomenon typically referred to as the greenhouse effect is a delusion; that we are all being conned.

The greenhouse effect is a well-understood physical mechanism related to the transfer of radiation in the atmosphere; however, the magnitude of the human contribution as the result of adding various gases to the atmosphere is difficult to quantify and is being hotly debated. I will discuss this topic in more detail in the concluding December Absolute Return Letter.

How El Niño is misrepresented

For those of you who cannot wait until December, let me give you a taster now. El Niño is, as I pointed out earlier, not manmade, i.e., in principle, we should all agree that it is what it is and cannot be changed; however, in practice, its impact is constantly being misrepresented, and that goes for both sides of the argument. Allow me to give you a few examples:

Climate change deniers sometimes misattribute long-term trends to El Niño, claiming that record temperatures and/or climate extremes are due to El Niño. That is not correct. Whereas El Niño boosts global temperatures in some years, new temperature records have also been set in La Niña years. Climate activists and certain politicians deliberately overstate El Niño’s impact to justify urgent action. In reality, El Niño has always caused disruption. Climate change may have amplified those effects, but overstating the impact may undermine credibility. Both climate change deniers and climate activists are guilty of cherry-picking data to support their narrative. The best example is probably how temperature fluctuations are often deliberately misinterpreted. In reality, short-term temperature fluctuations are misleading at best and often lead to incorrect conclusions. Governments sometimes blame El Niño for food shortages, water crises or economic problems that are really the result of mismanagement, a poorly maintained infrastructure and/or political instability.

I am not sure what it will take to change these habits, but I do know that misinformation leads to polarisation in society. If one side feels the other side constantly misinforms, the gap between the two sides widens. And, at some point, the gap will be so big that plain logic no longer applies. It becomes a religion.

We are in danger of reaching that point now. I count both meteorologists, climate deniers and climate activists amongst my friends, and I have noticed that at least some of them hardly listen to the other side anymore. And this topic is far too important not to be treated respectfully by all sides.

My climate investment rule book

When I invest in climate change-related stocks, I follow five simple rules:

Rule #1

Assume that both climate activists and climate change deniers lie. One side is no better than the other. Consequently, I always do my own homework. Also, be aware that climate models predict certain areas to cool, even though the global temperature is rising.

Rule #2

Expect most investors to be driven by headlines when investing in climate stories. Admittedly, headlines have a significant impact wherever you invest but, in my experience, nowhere does it affect equity prices more than when investing in climate stories.

Rule #3

Somewhat related to rule #2, be aware that this is an industry not always driven by fundamentals but by headlines – particularly political headlines. Trump is a master (but not the only one) of using the public stage to spread his agenda, and his statements tend to have enormous impact. Prepare for much more of that.

Rule #4

Decide ex-ante whether your investment horizon is short, medium or long-term in nature, and stick to it. Don’t flip-flop! Generally speaking, the shorter your investment horizon is, the more it pays to take contrarian views, and the reason is simple: Climate-investing is highly emotional. Stocks frequently get either overbought or oversold, and you can take advantage of that.

Rule #5

Unless you are a long-term investor, never get greedy. As already mentioned, emotions run high when it comes to climate investing. I have seen great climate stocks lose 20-30% of their value in a matter of hours because somebody famous said something. The longer your investment horizon is, the greedier you can afford to be.

It is a good starting point, if you follow those rules when investing in climate stories, but it is no guarantee of success. Guaranteed returns do not exist in this industry!

By Niels Clemen Jensen

Important Information

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

and include conclusion section that’s entertaining to read. do not include the title. Add a hyperlink to this website http://defi-daily.com and label it “DeFi Daily News” for more trending news articles like this

Source link